UNIVERSITY OF KOBLENZ

Universitätsstraße 1

56070 Koblenz

From its beginnings as support on the sidelines, cheerleading has developed into a serious competitive sport. In Germany alone, around 21,000 cheerleaders are active, and around 10 million worldwide.

In addition to gymnastics elements, the competitions also include so-called 'stunts', in which the 'bases' throw the mostly female, lighter 'flyers' into the air. The flyers try to perform the most difficult figures, such as 'cupie', 'full-up' or 'pop-over', with as few mistakes as possible.

"We know from scientific studies that injuries sometimes occur during such stunts, but we still know very little about the biomechanical causes," says lead author Dr Andreas Müller from the University of Koblenz, summarising the current state of research. Müller, who completed his doctorate in sports science at the University of Koblenz, was an active cheerleader himself, which also inspired him to conduct the study (DOI: 10.3389/fspor.2024.1419783).

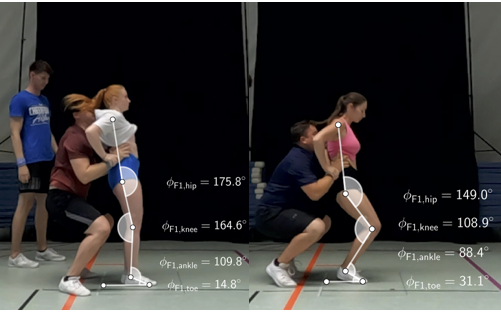

His team invited 15 top-level athletes from the Middle Rhine region to perform one of the simpler stunts - the so-called 'pop-off' (see picture) - under controlled conditions. The statistical analysis was carried out by Dr Robert Rockenfeller, currently Professor of Mathematics at the University of Koblenz.

"We performed stunts with different combinations of base and flyer, as well as before and after a tiring cardio workout, to find out which factors influence the hardness of the landing," Müller continues.

A total of hundreds of jumps were scientifically analysed, and the research group was particularly interested in the maximum ground reaction force, i.e. the time of the hardest impact.

"We had expected that tired athletes would land more uncleanly and therefore harder than rested athletes; however, this hypothesis was not confirmed. Instead, we were able to show that it is primarily the landing behaviour of the thrown flyer and less the catching behaviour of the base that determines the hardness of the hit," explains Rockenfeller. "We hope that our results can be used to adapt training and competition conditions in such a way that the risk of injury can be minimised."

By 2032, the research team hopes to further uncover the biomechanical principles of landings. For example, more precise resolution of base-flyer interaction, limb accelerations and internal joint forces will be measured or calculated using computer models.